Property insurers and reinsurers all have a dataset that is simultaneously:

It’s worth exploring how a historical database of claims can be all three things at once.

The history of claims paid by an underwriting organization is a fundamental collection of information, and from the very beginning of insurance in those smoky London coffeehouses in the 17th century they have been meticulously kept and guarded. They represent the sum-total of a company’s experience. Such information does not come cheaply though – every single claim was paid for in straight cash, including some monumental losses. Such corporate memory must be kept away from competitors because it's frequently hard experience that gives insurers a competitive edge – twice shy is more profitable than twice bitten.

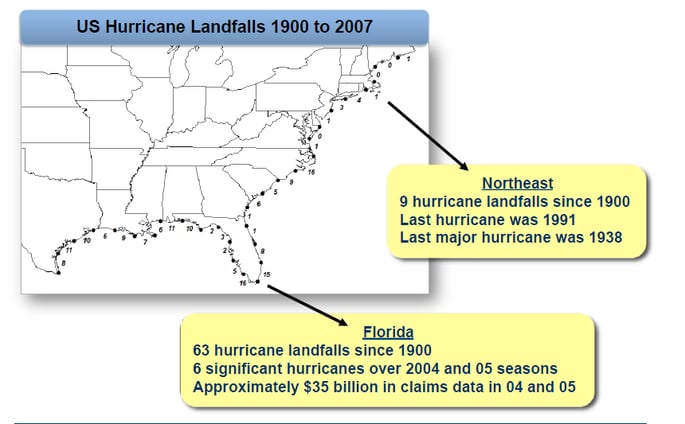

Claims history, along with full policy history, are the core datasets used for designing underwriting guidelines and business rules. Actuaries spend a lot of time with these archives, to say the least. But in the case of property insurance, and more specifically, natural catastrophe coverage, history is an inadequate guide. The Toronto flooding from 2013 was caused by 90mm of rain in one day, more than both “the previous same-day rainfall record of 29.2 mm in 2008 and … the roughly 70 mm monthly average for July”. It was a completely unpredictable event based on historical records. Another example is the annual estimation of impending wind losses from Atlantic hurricanes, a wildly difficult prediction to make based on history, as shown by this graphic:

© 2011 Karen Clark & Company

Natural events that wreak damage to property are, by their very nature, not bound by anything that has been witnessed in the past few hundred years, let alone insured by a single carrier in the past century.

However, there is information yet to be gained from these comprehensive catalogs of losses, especially for property losses. New techniques in geospatial analytics can convert a vast database into a map that can be incorporated into a geospatial analytic engine. Leveraging claims data in this way can lead to new insights into how losses can be modeled, by location, in a way that is immediate and intuitive, and can enable better portfolio management through better underwriting and better accumulation. In upcoming posts, I will explore how the incorporation of geospatially compiled claims into Risk Scoring is a fresh way to unearth further riches from these vast mines of knowledge.

.png?width=500&name=InsitePro4%20(1).png)

Comment Form